America’s forgotten conservationist, Ernest Thompson Seton, is celebrated in the History Museum exhibit Wild at Heart: Ernest Thompson Seton. Today, let’s take a short walk through the exhibit, supplemented by what you’ll read and what you’ll see. (All photos are by Blair Clark, New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs.)

As you head upstairs to the Albert and Ethel Herzstein Changing Exhibitions Gallery, you’ll quickly notice something’s afoot: Hey, there are wolves on the walls!

Upon entering into the (air-conditioned!) cool, we get our first introduction to Seton.

In 1893, on the winter plains of New Mexico, a drama played out between a wolf pack and a wolf hunter named Ernest Thompson Seton. Through his interaction with the wild canines, Seton underwent a personal transformation, changing from their persecutor to their protector, becoming a leading proponent of wildlife conservation. Seton reached an international audience of millions through his drawings, paintings, books and lectures. He wrote the first realistic animal story and established important principles for the sciences of animal behavior and ecology. His passion for self-reliance, ethics, and outdoor youth education led him to become a founder of the worldwide Boy Scout movement. Seton’s insights sparked a revolution in our perceptions of wild nature, provided a model for environmentalism, and inspired generations of youths and adults to take to the outdoors for recreation, adventure, and solace.

In 1893, on the winter plains of New Mexico, a drama played out between a wolf pack and a wolf hunter named Ernest Thompson Seton. Through his interaction with the wild canines, Seton underwent a personal transformation, changing from their persecutor to their protector, becoming a leading proponent of wildlife conservation. Seton reached an international audience of millions through his drawings, paintings, books and lectures. He wrote the first realistic animal story and established important principles for the sciences of animal behavior and ecology. His passion for self-reliance, ethics, and outdoor youth education led him to become a founder of the worldwide Boy Scout movement. Seton’s insights sparked a revolution in our perceptions of wild nature, provided a model for environmentalism, and inspired generations of youths and adults to take to the outdoors for recreation, adventure, and solace.

Heading counter-clockwise, we learn of Seton’s background and his first foray into New Mexico.

On October 22, 1893, 33-year-old Canadian naturalist and artist Ernest Thompson Seton arrived in Clayton, New Mexico. He had been hired to hunt wolves. As buffalo, antelope and deer had been eliminated through hunting and habitat loss, wolves turned to killing cattle. They threatened the livelihood of ranchers. For the next three months as Seton rode the rangeland of Union County, he thought a great deal about wilderness, wildlife and our relationship to the land. The wolves he hunted were becoming his teachers. Seton hunted a wolf pack along the Corrumpa Creek (“Currumpaw”) which flows east from Capulin Volcano National Monument, an ideal area for wildlife. He wrote: “The place seemed uninviting to a stranger from the lush and fertile prairies of Manitoba, but the more I saw of it the more it was revealed as a paradise.”

On October 22, 1893, 33-year-old Canadian naturalist and artist Ernest Thompson Seton arrived in Clayton, New Mexico. He had been hired to hunt wolves. As buffalo, antelope and deer had been eliminated through hunting and habitat loss, wolves turned to killing cattle. They threatened the livelihood of ranchers. For the next three months as Seton rode the rangeland of Union County, he thought a great deal about wilderness, wildlife and our relationship to the land. The wolves he hunted were becoming his teachers. Seton hunted a wolf pack along the Corrumpa Creek (“Currumpaw”) which flows east from Capulin Volcano National Monument, an ideal area for wildlife. He wrote: “The place seemed uninviting to a stranger from the lush and fertile prairies of Manitoba, but the more I saw of it the more it was revealed as a paradise.”

The gray wolf (Canis lupus) likely lived in this area for thousands of years. Seton found that wolves in northern New Mexico could weigh up to 100 pounds, although most weighed less, reaching the size of German shepherd dogs. In 1974, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed the gray wolf as “Endangered” in the lower 48 states and Mexico. Listing and attempts at de-listing wolf populations have remained contentious issues over the decades.

Seton’s effort to kill a wolf he named “Blanca,” then her mate, the pack-leader “Lobo,” turned into a horrific experience, one that left him asking, in his nature journal, “Why?” He never killed another wolf, returning instead to his home in Toronto, where he wrote a story about the hunt in which he cast himself as the villain. Lobo and Blanca – capable of courage, honor, and love – became the heroes. The story, “The King of Currumpaw,” began to change the way North Americans viewed wildlife, and marked an important turning point for the wildlife conservation movement.

From “The King of Currumpaw”:

From “The King of Currumpaw”:

As I drew near a great grizzly form arose from the ground, vainly endeavoring to escape, and there revealed before me stood Lobo, King of the Currumpaw, firmly held in the traps. Poor old hero, he had never ceased to search for his darling, and when he found the trail her body had made he followed it recklessly, and so fell into the snare prepared for him…Yet, when I went near him, he rose up with bristling mane and raised his voice, and for the last time made the cañon reverberate with his deep bass roar, a call for help, the muster call of his band. But there was none to answer him…

For the next 10 years, Seton combined intense wildlife study with developing a close relationship with Canada’s First Nations peoples. When not traveling, he lived in Toronto or New York City, developing his career as an illustrator and naturalist. He also began writing short fiction and natural history observations. He would later publish around 40 books that would sell more than 2 million copies.

Seton published articles and monographs on wildlife from an early age. “Roger Tory Peterson freely acknowledges that the idea for his now familiar technique of identifying birds in the field came from Seton…In this way, Seton provided some of the impetus that has led to the present era of enjoyment and understanding of birds.” Robert W. Nero, American Ornithologists’ Union, 1975.

Seton published articles and monographs on wildlife from an early age. “Roger Tory Peterson freely acknowledges that the idea for his now familiar technique of identifying birds in the field came from Seton…In this way, Seton provided some of the impetus that has led to the present era of enjoyment and understanding of birds.” Robert W. Nero, American Ornithologists’ Union, 1975.

Seton gained increasing recognition for his illustrations and stories about wildlife throughout the 1890s. He used this celebrity to become a leading advocate for preservation of all wild creatures. Like Henry David Thoreau, he believed that the continued existence of wild nature was vital to our own survival on both a physical and moral level.

“There will always be wild land not required for settlement; and how can we better use it than by making it a sanctuary for living Wild Things that afford pure pleasure to all who see them?” Lives of the Hunted, 1901

By 1905, Seton was one of the most popular lecturers in the United States, Canada, and England. He also turned his attention to creating scientific works. Combining his knowledge of mammalogy, ecology, and ethology (animal behavior) and study with native peoples, his first major nonfiction work, Lives of Northern Animals, won immediate acclaim from biologists.

In 1900, Seton purchased a woodland estate near Greenwich, Connecticut, naming it Wyndygoul, for a Seton family estate in Scotland. It was subject to occasional vandalism by local boys. Instead of calling in law enforcement, Seton invited his young antagonists to join him for a weekend campout on March 28-29, 1902. Seton told compelling stories of the West and taught them the basic skills of “Woodcraft.”

He ran a more formal weekend camp at Summit, New Jersey at the beginning of July. At the same time, he wrote a six-part series for Ladies’ Home Journal, “Ernest Thompson Seton’s Boys.” Thousands of boys joined what became known as the “Woodcraft” movement. The camps and articles established principles of outdoor education influencing the programming of summer youth camps for the next century. His main intent was to help youths connect with nature — an aim the History Museum shares in both the design of the exhibit’s interior space with trunks from real aspen trees (where story-tellers will enthrall children and families in upcoming events) and its supplemental programs that include an urban bird hike and nature-journaling workshops.

He ran a more formal weekend camp at Summit, New Jersey at the beginning of July. At the same time, he wrote a six-part series for Ladies’ Home Journal, “Ernest Thompson Seton’s Boys.” Thousands of boys joined what became known as the “Woodcraft” movement. The camps and articles established principles of outdoor education influencing the programming of summer youth camps for the next century. His main intent was to help youths connect with nature — an aim the History Museum shares in both the design of the exhibit’s interior space with trunks from real aspen trees (where story-tellers will enthrall children and families in upcoming events) and its supplemental programs that include an urban bird hike and nature-journaling workshops.

Other men took notice of Seton’s success with the “Woodcraft Indians.” Daniel Carter Beard (American boys’ writer and artist) announced the formation of the rival organization, “Sons of Daniel Boone,” in April 1905. Robert Baden-Powell (British hero of the Second Boer War in South Africa) organized an experimental camp for boys in England in 1908, based in part on the Seton model. He called his organization the Boy Scouts.

Both Beard and Baden-Powell freely adopted many of Seton’s ideas, often without giving Seton credit. Over time, Seton’s Woodcraft movement faded while the Boy Scout movement thrived. Worldwide, more than 350 million boys, girls, and their families have taken part in Scouting over the past century.

As part of his own efforts through Woodcraft, Seton made illustrations and items to show Scouts and Woodcrafters how to make their own items. He handcrafted a number of items for his own use.

As part of his own efforts through Woodcraft, Seton made illustrations and items to show Scouts and Woodcrafters how to make their own items. He handcrafted a number of items for his own use.

Seton wrote and edited an edition of Boy Scouts of America, Handbook for Boys on display in the exhibit. In it, he combined his Woodcraft writings with the Scout writings of Baden-Powell. The Boy Scout Handbook has been issued in many subsequent editions over the past century with millions of copies printed.

On February 8, 1910, businessman and newspaper owner W. D. Boyce incorporated the Boy Scouts of America. On June 21, Edgar M. Robinson of the YMCA became the temporary head of the organization. He recruited Seton as its most public standard-bearer. Beginning on August 16, Seton led the first official camp of the Boy Scouts of America at Silver Bay, New York. Shortly afterward, Seton was given the honorary title, Chief Scout. He worked tirelessly to establish Scouting as an American institution.

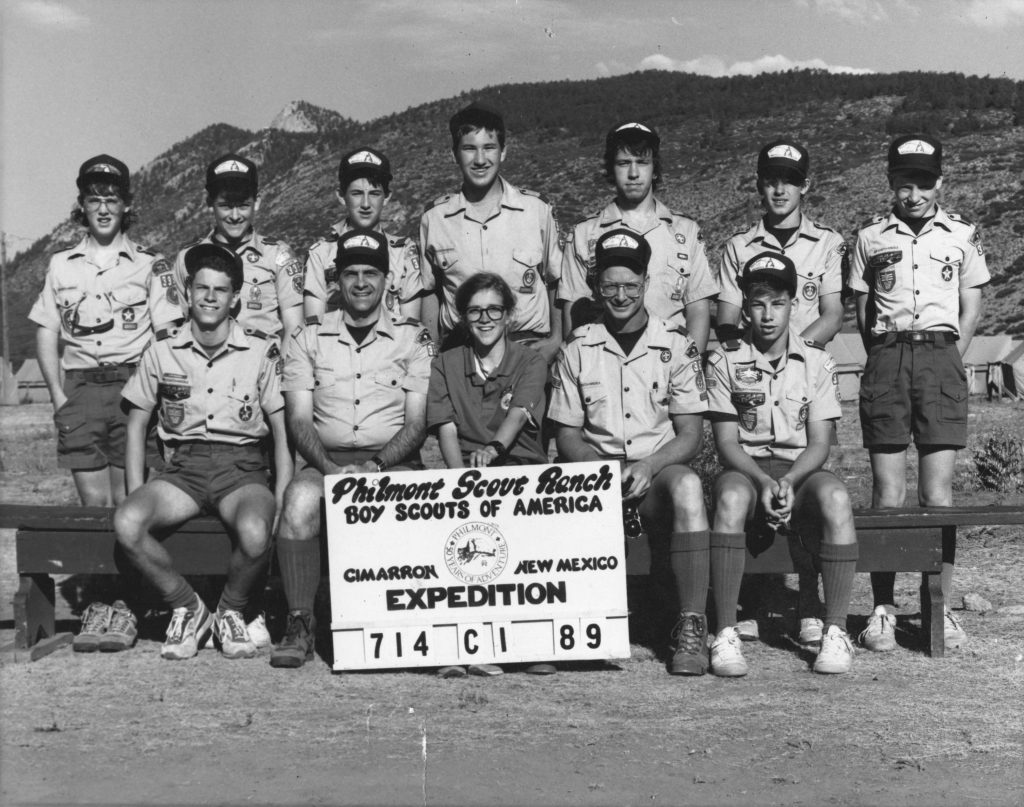

Though Seton eventually parted ways with the Boy Scouts, he remained a tireless champion of outdoors education for youths and for conservation. Some of that work can be seen every summer in Cimarron, N.M., where Boy Scouts gather at the Philmont Scout Ranch.

Beginning in 1930, Seton built a “castle” outside of Santa Fe on what he thought of as “The Last Rampart of the Rockies” and what is still known today as Seton Village. The castle burned down during its renovation by the Academy for the Love of Learning, our partner in this exhibit, but the Academy is offering tours of its ruins, along with Seton-related programming on three dates. The first, Aug. 14, coincides with Seton’s 150th birthday and includes tales around a campfire.

Seton died in Santa Fe on October 23, 1946, almost exactly 53 years after his first trip to Clayton. In all that time, Seton had never forgotten the King of Currumpaw. By forcing Seton to ask WHY, Lobo helped him on his journey from wolf killer to student of the Buffalo Wind. Seton made a transformation within himself, putting the best of what he had learned to work its way in the world – where it is working still. As you leave the exhibit, we ask you to ponder this:

Seton would urge you to experience wild nature: Photograph wildlife. Draw the landscape. Write journal entries about your feelings for glorious outdoors New Mexico. And always, keep the love of learning alive!

Enter

Enter  “But the thread that runs through our culture in every community is we have grace in the face of adversity,” she said. “We have love in the face of hate. We have perseverance and a deep and abiding sense of joy. We hope when you see the faces in this exhibit, they will speak to you.”

“But the thread that runs through our culture in every community is we have grace in the face of adversity,” she said. “We have love in the face of hate. We have perseverance and a deep and abiding sense of joy. We hope when you see the faces in this exhibit, they will speak to you.” Among the people it features are Cedric and Merdest Billingsley Bradford (left), longtime operators of the U-Tote-Em Grocery Store in Las Cruces and community activists who devoted time to Planned Parenthood, the NAACP, and Las Cruces’ public schools.

Among the people it features are Cedric and Merdest Billingsley Bradford (left), longtime operators of the U-Tote-Em Grocery Store in Las Cruces and community activists who devoted time to Planned Parenthood, the NAACP, and Las Cruces’ public schools.

Opening this weekend, The Threads of Memory: Spain and the United States (El Hilo de la Memoria: Espana y los Estados Unidos) weaves the story of Spain’s first 300 years in the Americas. The History Museum marks the U.S. debut of 138 rare and precious documents, maps, illustrations and paintings — but it’s only here until Jan. 9, 2011, so get it on your calendar. (You’ll also enjoy the 12 weeks of lectures, concerts and Chautauqua performances accompanying it; every one of them is free.)

Opening this weekend, The Threads of Memory: Spain and the United States (El Hilo de la Memoria: Espana y los Estados Unidos) weaves the story of Spain’s first 300 years in the Americas. The History Museum marks the U.S. debut of 138 rare and precious documents, maps, illustrations and paintings — but it’s only here until Jan. 9, 2011, so get it on your calendar. (You’ll also enjoy the 12 weeks of lectures, concerts and Chautauqua performances accompanying it; every one of them is free.) Here, the installation crew buzzes in the part of the gallery where we’ve hung Giuseppe Perovani’s 1796 portrait of George Washington. Many Americans are unaware of the critical role Spain played in helping to win the Revolutionary War. Perovani lived for several years in the United States and, in 1801, with the prestige he had earned, went to Cuba on contract with Archbishop Espejo to help decorate the Cathedral of Havana. He also worked as a teacher there and, afterward, moved back to Mexico, where he became an academic of merit and second director of painting in the Academia de Bellas Artes de San Carlos.

Here, the installation crew buzzes in the part of the gallery where we’ve hung Giuseppe Perovani’s 1796 portrait of George Washington. Many Americans are unaware of the critical role Spain played in helping to win the Revolutionary War. Perovani lived for several years in the United States and, in 1801, with the prestige he had earned, went to Cuba on contract with Archbishop Espejo to help decorate the Cathedral of Havana. He also worked as a teacher there and, afterward, moved back to Mexico, where he became an academic of merit and second director of painting in the Academia de Bellas Artes de San Carlos. Dr. Frances Levine (left), director of the museum, points to and talks about one of her favorite pieces in the exhibit,a 1786 agreement, hand-written in the Palace of the Governors, between

Dr. Frances Levine (left), director of the museum, points to and talks about one of her favorite pieces in the exhibit,a 1786 agreement, hand-written in the Palace of the Governors, between  Some of the media members who came to our preview was the

Some of the media members who came to our preview was the  Among EF’s interviews was one with

Among EF’s interviews was one with  Dr. Levine and Josef Diaz, the museum’s curator of Southwest and Mexican Art and History, examine an illustration of La Belle. The image is the main “brand” of the exhibit; see it above as part of the exhibit title.)

Dr. Levine and Josef Diaz, the museum’s curator of Southwest and Mexican Art and History, examine an illustration of La Belle. The image is the main “brand” of the exhibit; see it above as part of the exhibit title.) Josef Diaz; Mayor Coss; and Dr. Levine.

Josef Diaz; Mayor Coss; and Dr. Levine.

In 1893, on the winter plains of New Mexico, a drama played out between a wolf pack and a wolf hunter named Ernest Thompson Seton. Through his interaction with the wild canines, Seton underwent a personal transformation, changing from their persecutor to their protector, becoming a leading proponent of wildlife conservation. Seton reached an international audience of millions through his drawings, paintings, books and lectures. He wrote the first realistic animal story and established important principles for the sciences of animal behavior and ecology. His passion for self-reliance, ethics, and outdoor youth education led him to become a founder of the worldwide Boy Scout movement. Seton’s insights sparked a revolution in our perceptions of wild nature, provided a model for environmentalism, and inspired generations of youths and adults to take to the outdoors for recreation, adventure, and solace.

In 1893, on the winter plains of New Mexico, a drama played out between a wolf pack and a wolf hunter named Ernest Thompson Seton. Through his interaction with the wild canines, Seton underwent a personal transformation, changing from their persecutor to their protector, becoming a leading proponent of wildlife conservation. Seton reached an international audience of millions through his drawings, paintings, books and lectures. He wrote the first realistic animal story and established important principles for the sciences of animal behavior and ecology. His passion for self-reliance, ethics, and outdoor youth education led him to become a founder of the worldwide Boy Scout movement. Seton’s insights sparked a revolution in our perceptions of wild nature, provided a model for environmentalism, and inspired generations of youths and adults to take to the outdoors for recreation, adventure, and solace. On October 22, 1893, 33-year-old Canadian naturalist and artist Ernest Thompson Seton arrived in Clayton, New Mexico. He had been hired to hunt wolves. As buffalo, antelope and deer had been eliminated through hunting and habitat loss, wolves turned to killing cattle. They threatened the livelihood of ranchers. For the next three months as Seton rode the rangeland of Union County, he thought a great deal about wilderness, wildlife and our relationship to the land. The wolves he hunted were becoming his teachers. Seton hunted a wolf pack along the Corrumpa Creek (“Currumpaw”) which flows east from Capulin Volcano National Monument, an ideal area for wildlife. He wrote: “The place seemed uninviting to a stranger from the lush and fertile prairies of Manitoba, but the more I saw of it the more it was revealed as a paradise.”

On October 22, 1893, 33-year-old Canadian naturalist and artist Ernest Thompson Seton arrived in Clayton, New Mexico. He had been hired to hunt wolves. As buffalo, antelope and deer had been eliminated through hunting and habitat loss, wolves turned to killing cattle. They threatened the livelihood of ranchers. For the next three months as Seton rode the rangeland of Union County, he thought a great deal about wilderness, wildlife and our relationship to the land. The wolves he hunted were becoming his teachers. Seton hunted a wolf pack along the Corrumpa Creek (“Currumpaw”) which flows east from Capulin Volcano National Monument, an ideal area for wildlife. He wrote: “The place seemed uninviting to a stranger from the lush and fertile prairies of Manitoba, but the more I saw of it the more it was revealed as a paradise.” From “The King of Currumpaw”:

From “The King of Currumpaw”: Seton published articles and monographs on wildlife from an early age. “Roger Tory Peterson freely acknowledges that the idea for his now familiar technique of identifying birds in the field came from Seton…In this way, Seton provided some of the impetus that has led to the present era of enjoyment and understanding of birds.” Robert W. Nero, American Ornithologists’ Union, 1975.

Seton published articles and monographs on wildlife from an early age. “Roger Tory Peterson freely acknowledges that the idea for his now familiar technique of identifying birds in the field came from Seton…In this way, Seton provided some of the impetus that has led to the present era of enjoyment and understanding of birds.” Robert W. Nero, American Ornithologists’ Union, 1975. He ran a more formal weekend camp at Summit, New Jersey at the beginning of July. At the same time, he wrote a six-part series for Ladies’ Home Journal, “Ernest Thompson Seton’s Boys.” Thousands of boys joined what became known as the “Woodcraft” movement. The camps and articles established principles of outdoor education influencing the programming of summer youth camps for the next century. His main intent was to help youths connect with nature — an aim the History Museum shares in both the design of the exhibit’s interior space with trunks from real aspen trees (where

He ran a more formal weekend camp at Summit, New Jersey at the beginning of July. At the same time, he wrote a six-part series for Ladies’ Home Journal, “Ernest Thompson Seton’s Boys.” Thousands of boys joined what became known as the “Woodcraft” movement. The camps and articles established principles of outdoor education influencing the programming of summer youth camps for the next century. His main intent was to help youths connect with nature — an aim the History Museum shares in both the design of the exhibit’s interior space with trunks from real aspen trees (where  As part of his own efforts through Woodcraft, Seton made illustrations and items to show Scouts and Woodcrafters how to make their own items. He handcrafted a number of items for his own use.

As part of his own efforts through Woodcraft, Seton made illustrations and items to show Scouts and Woodcrafters how to make their own items. He handcrafted a number of items for his own use.