During the fall, Photo Archives digitized and posted some select sets of photo material. Additions to our digital collections include:

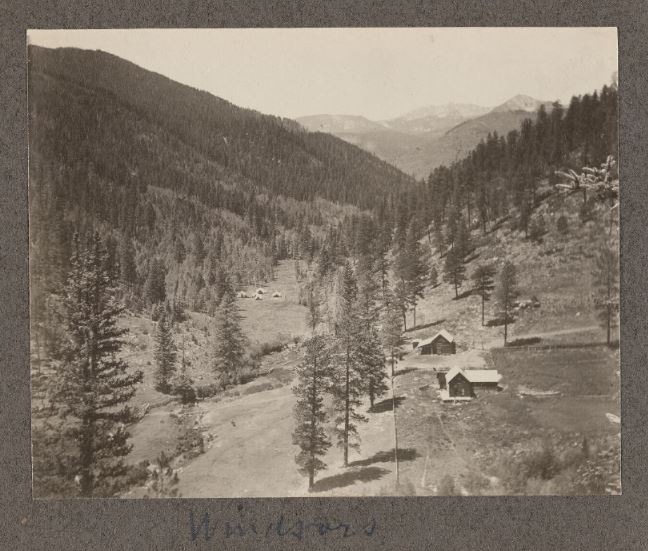

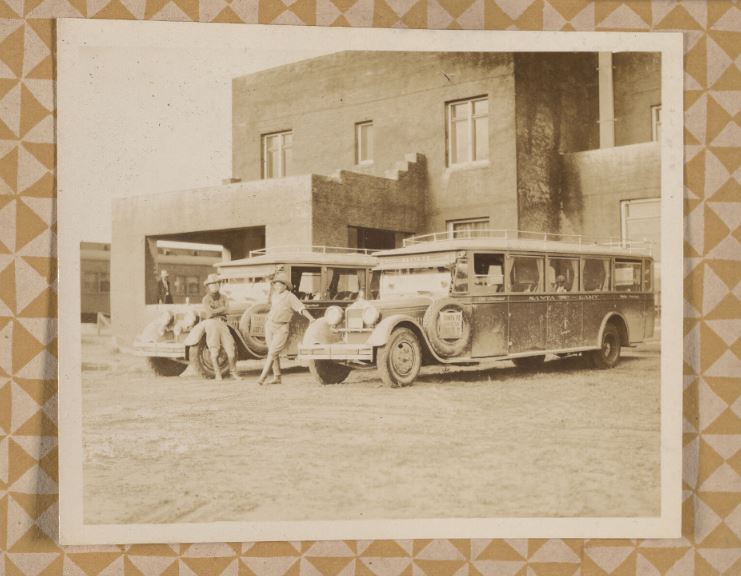

Dominguez and Escalante

This collection contains exhibition prints created by photographers Siegfried Halus and Greg Mac Gregor, who carried out a rephotography project to document the contemporary changes to the landscape that friars Domínguez and Escalante traversed in on their 1776 expedition. While the friars initially sought to find an overland route connecting Santa Fe with Alta California, Domínguez and Escalante, along with a group of several people, eventually circled what is now known as the Four Corners area and were the first non-Indigenous people to cross the Grand Canyon.

Related Book: In Search of Dominguez and Escalante – Museum of New Mexico Press

Pilgrimage to Chimayo

This collection contains prints and audio recordings from a travelling exhibition depicting the annual pilgrimage to El Santuario de Chimayó in New Mexico. Bringing in roughly 300,000 visitors, this site has become one of the most important Catholic pilgrimage centers in the United States. The exhibition was an outcome of a collaborative documentary project including the photographers Sam Howarth, Cary Herz, Miguel Gandert, and Oscar Lozoya and oral historians Enrique Lamadrid and Troy Fernandez. They wanted to better document the annual event through the perspectives of its participants.

Digital Collection: Pilgrimage to Chimayó: A Contemporary Portrait of a Living Tradition Photographs

Digital Collection: Pilgrimage to Chimayo Audio

Exhibition: Chimayo A Tradition of Faith – New Mexico History Museum

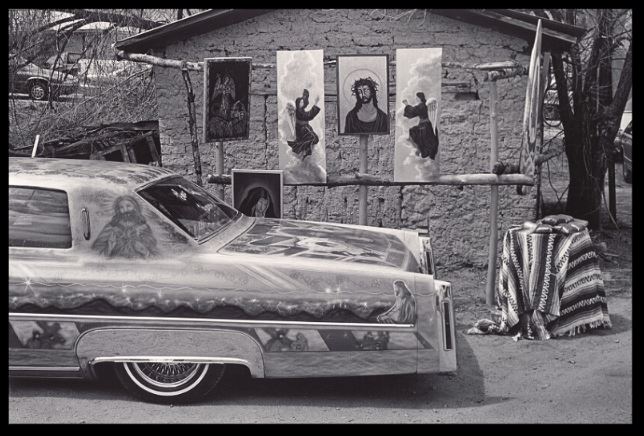

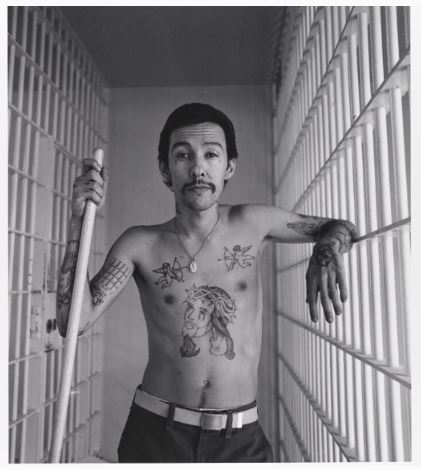

Douglas Kent Hall

This newly digitized collection consists of a series of prints from photographer Douglas Kent Hall’s estate. These photographs are on a variety of New Mexico and southwestern subjects with a subset on the Los Matachines de Alcalde. Hall’s work in our collection also includes images related to the Border, his “In Prison” work, and a series of portraits of New Mexicans featuring artists and writers.

Digital Collection: Douglas Kent Hall Photograph Collection

Finding Aid: Douglas Kent Hall Photographs | New Mexico Archives Online

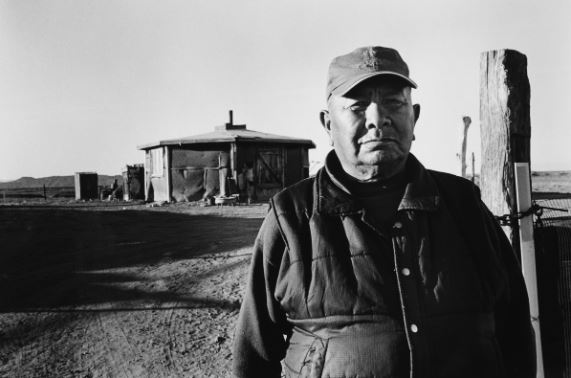

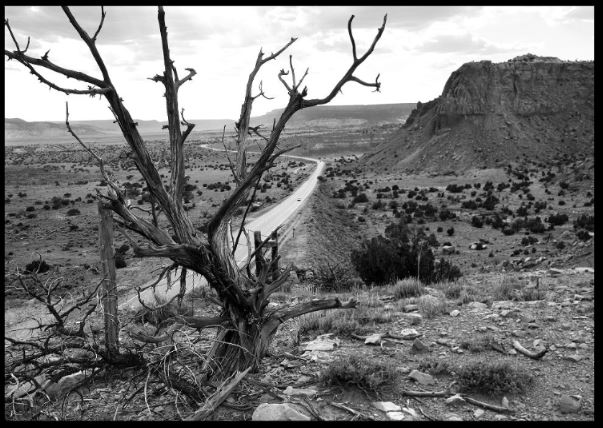

CarlanTapp’s A Question of Power

A finding aid was created earlier this year for this documentary photography project around the Navajo Nation, coal mining, and the Desert Rock Power Plant. A digital collection featuring Tapp’s exhibition prints is now available.

Digital Collection: Carlan Tapp: Doodá Desert Rock Photograph Collection

Finding Aid: Doodá Desert Rock: Naamehnay Project Collection | New Mexico Archives Online